Bonjour! Morning air on the way from our hotel to the “Not New Now” or the sixth Marrakech Biennale was filled with a mixture of hot dust, a motor rollers’ loud noise and a delicate smell of spices.

When we arrived at a relatively new and central part of Marrakech called Gueliz, we found a Soviet architecture style building where Marrakech Biennale office resides. Here, on 62 Yugoslavia str., our exploration of Marrakech Biennale 6 began. Wandering around, we found several rooms dedicated to video art, mixed media art and installations on the roof terrace. The unexpected morning emptiness in the building with no invigilators or visitors was charming, creating a setting for an intimate viewing of the works by Aida Muluneh, Emanuel Tegene, Ephrem Solomon, Tamrat Gezahengne, among others.

The curator of the Biennale, Reem Fadda, presented her curatorial concept under the ambiguous title “Not New Now” (“NOT new now?” or “not new NOW”? we wondered…) Regrettably, we were not present during the press conference and no catalogs were available at the time of our visit. The cheerful and friendly assistant curator, Ilaria Conti, provided us with the Biennale map and a short press release, which became our only clues to Fadda’s exhibition described as “an open-end question about the future and the past.”

The artworks and projects were scattered around Marrakech seemingly as a treasure hunt. We would run with a map from one spot to another filled with an excitement to find another Biennale sign indicating that we were at the right spot.

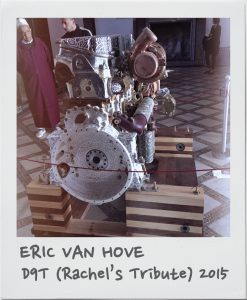

Our second “treasure” according to the map was Palais El Bahia. A stunning 19th century stunning palace with zellige tiles and labyrinthine layout was hosting the contemporary art exhibition. The first piece we found in the foyer was Eric Van Hove’s “D9T (Rachel’s Tribute)”, a bulldozer motor replica that was used to raze Palestinian towns. The sculpture was echoing the intricate and ornate carvings of the palace. It paid a memory tribute to young American activist Rachel Corrie (1979-2003), who placed herself between bulldozer and the house of Palestinian doctor, but she didn’t win the battle against the political machine.

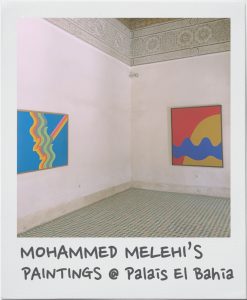

The geometric compositions by Mohammed Melehi, displayed against the traditional interiors of the palace, challenge the perception of Western modernism and open a dialogue with the past. The heritage was made by anonymous artists, who created meticulously ornate mosaics. We could have looked at it for days, but eventually Al Loving’s fabric and Sam Gilliam’s draped, three-dimensional abstract paintings distracted our attention from the mesmerizing ornaments on the ceiling and floor. For me, the artworks’ implication of the form and color was hinting at Oriental folk textiles.

It was getting hot as we went through the labyrinth of Palais El Bahia and we continued our contemporary art “discoveries”: Manthia Diawara, Mohamed Chabaa, Khalil El Ghirib, Djibril Diop Mambety, Talal Afifi, Oscar Murillo and Melvin Edwards’s pieces embedded in the past.

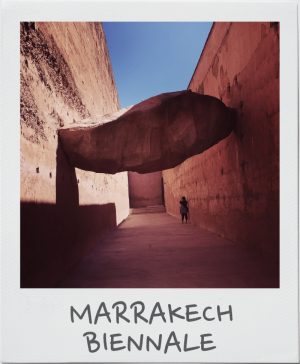

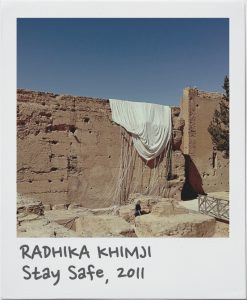

After “digesting” the first part of the exhibition, we couldn’t resist the temptation of tasting delicious Moroccan couscous and meat dishes cooked in tagines. After a short break, we headed towards 16th century Palais El Badii. This site turned to be my favorite venue of Marrakech Biennial 6. At the entrance, one could find Fatiha Zemmouri’s ”Sheltered… from Nothing” – a meteor-like sculpture, stuck between two walls. It was hovering above the visitors’ heads as a reminder of an ancient history. The sculpture neighbored Radhika Khimji’s abandoned parachute “Stay Safe”, which becomes a metaphor for the precautious state of being between two temporalities: escape and arrival. In the current context of migration crisis this parachute has landed in a safe heritage location –Palais El Badii and Les Citernes de la Koutoubia with no wars or danger. Secured… “no one is watching”. No one except “Heel”, “Amulet”, “Head”, “Belly”, “Gutter”, “Grid”, “Shoulder” the chatty sculptures by Jumana Manna leaning upon the wall. The sculptures theatrically composed in the sunny arena of the palace reconnect the time when during the five centuries of the existence of the palace, the rulers, visitors, diplomats, and conquerors’ left their traces in this historical site.

Saba Innab’s interest in de-territorialization resulted in three-meter high sculptures “Time measured by distance (I)” and “Time Measured by distance (II)”. Whereas the first is “the void between the two shores is constructed as a volume that links the highest point between the two shores – the rock of Gibraltar (426 m) and Jebel Musa (842 m Tangier)”. The latter is a white oxymoronic sculpture investigates a “link between verticality and horizontality; tunnels to pillars, towers to borders”. The historical heritage relationship with the contemporanity in the context of Palais El Badii unveiled new artists for me: Radika Khimji, Rachid Koraichi, Haig Aizazian, Radouan Mriziga, El Anatsui, Megumi Matsumara and Ahmed Mater.

The remaining four treasure locations of the Marrakech Biennale 6, marked in red on the map, were hidden for the most persistent visitors. Dar Si Said Palace, our third destination, was tucked away in one of the innumerable narrow streets of Marrakech. It turned out that the palace wasn’t as popular as Palais El Bahia and Palais El Badii and we could hardly see any visitors or museum staff. However, works of Mohamed Mourabiti, Mona Hatoum, Khalil Rabah and Dana Awartani rewarded our persistency in “hunting”.

The fourth destination on the map was Les Citernes de la Koutoubia. Despite the venue being an obvious tourist trap, the exhibition of video works was cleverly set in the dark and quiet chambers and corridors located below the ground. One of our favorite works on display was the video installation “Kwassa Kwassa” by Danish group Superflex tackling the complex political history of Mayotte – an island in the Indian Ocean, which is currently the most remote EU territory and thus a site of mass-migrations.

The last stop in our parcours was the Khalid Art Gallery. We kept passing the site several times, unable to find it, as there were no Biennale signs. The gallery hosted Naeem Mohaiemen’s installation consisting of 12 typewritten pages and photographs of his great uncle’s book. This venue of Marrakech Biennial left us in a bit confused state of mind, unable to understand how the context of the commercial antique shop for an artwork “responded to social – political urgency”.

The long day was over… It was nice to unwind on a roof terrace in the evening, looking into the clear sky full of stars… One doesn’t usually see stars in London; it’s such a different world over here. It’s simple, it’s warm, it’s colorful and it is full of traditions embedded in everyday life, where one sees donkeys carrying heavy loads in the streets – a perfect fairytale for a traveller from the West.

Trying hard not to romanticize our experience – of the exhibition and of the city – one thing became apparent. The majority of visitors we saw were groups of foreign tourists. While the exhibition was a true delight for us, inevitably the biggest challenge for the organizers will be to meaningfully engage with the local community. Using historical landmarks as exhibition venues often presents this challenge, whether it’s Marrakech, Istanbul or Havana.

Text and images by Vija Skangale

Vija Skangale is a recent graduate from MRes: Exhibition Studies, Central Saint Martins. Her main research focus is on transnationalism in the biennial context. In 2014 she worked at the Cubitt Gallery as part of the Archive Placement programme. She also has experience working in the private art sector. Currently, she lives in London and works at the University of the Arts.

Would you like to see your own report from a biennial published on our website? Learn how HERE.