Less than an hour on a bullet train North-West of Shanghai, in one of the most densely populated parts of the planet, lies the birthplace of Wu culture, the ancient city of Suzhou. First inhabited over 2500 years ago, the city grew to become the economic and cultural capital of the Ming Dynasty (1400–1700) during the Middle Ages. By the 13th century, Suzhou had established itself as the centre of the silk trade, a starting point in the flourishing economic and cultural umbilical cord that connected the region with the rest of Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Europe. Despite this rich history, Suzhou’s artistic status was overshadowed by Shanghai’s mythological rise as a burgeoning global powerhouse. Indeed, both in China and further afield, many associate Suzhou’s art scene with classical traditions: its Imperial era gardens, temples, fine crafts and the quaint canal system that criss-crosses the city. Against this developmental backdrop, the authorities in Suzhou backed plans for the creation of a new, periodical exhibition: Suzhou Documents.

The co-curators of the inaugural exhibition ‘Histories of a Global Hub,’ Zhang Qing (Founding Director of the Shanghai Biennial and Curatorial Head of the National Palace Museum in Beijing) and Roger M. Buergel (Artistic Director of documenta 12 (2007) and Director of the Johann Jacobs Museum in Zurich), set out to eschew what they saw as the ‘largely exhausted’ biennale format. Describing the latter as a ‘bouquet of arbitrary themes’ with an emphasis on spectacle, they argue for the value of depth and sensitivity in bringing together the ancient and modern in a sustainable, yet rigorous manner.

Their proposed alternative takes the form of an overlapping, ongoing series of exhibitions: a future-oriented ‘institution in its own right,’ and a move away from the symptomatology of ‘biennialization.’ Buergel and colleagues, as stated in the introduction to Suzhou Documents, are ‘keenly aware of the limits imposed on conventional exhibition-making’ by the drive to evade either the ‘confines of the museum’ or simply becoming another ‘biennale lookalike.’ As they put it, Qing and Buergel hope to attend to the ‘widespread inability to look at art properly.’ They lament a ‘top-down flip-flopping’ between art touted as ‘an appendage of the fashion and entertainment industries [and on the other hand] a therapy for alienated communities.’

Perhaps inevitably, the result did not entirely escape the tried-and-tested biennale set-up. The first Suzhou Documents presented a large-scale exhibition (featuring the work of over 40 artists), held peripatetically around the city at various historical and modern spaces. These included the famed Pu Garden, the popular Suzhou Silk Museum and Twin-Pagoda. Other venues were the Yan Wenliang Memorial Museum, and Wu Zuoren Art Museum. The main body of the exhibition was concentrated in the impressive Suzhou Art Museum: believed to be the oldest art museum in China (established in 1927 by gifted painter and art educator Yan Wenliang).

A clear attempt was made to create an immersive and participatory exhibition, the objet d’art frequently rubbed shoulders with arrangements of everyday objects, historical artefacts and archival ephemeral, photographs, texts, paintings and drawings. In a familiar intervention, Buergel and Qing placed contemporary furniture at various venues throughout the exhibition sites, recalling the display of antique Qing dynasty chairs, which artist Ai Weiwei collects, at Documenta 12 in 1997. The frequent display of historical works alongside the contemporary speaks to a curatorial remit of looking-back-to-look-forwards, something again seen in Buergel’s Documenta 12 offering. Qing concurs: ‘we can’t always look forwards… sometimes we need to look back.’ In the Chinese context, particularly in the decades following the Cultural Revolution, a rehashing of the past was discredited as a block to the onwards march towards communist hegemony. Today, the recognized importance of ‘soft power’ legitimizes the deft pairing of ancient and hyper-modern which constitutes the driving force of contemporary Chinese policy-making.

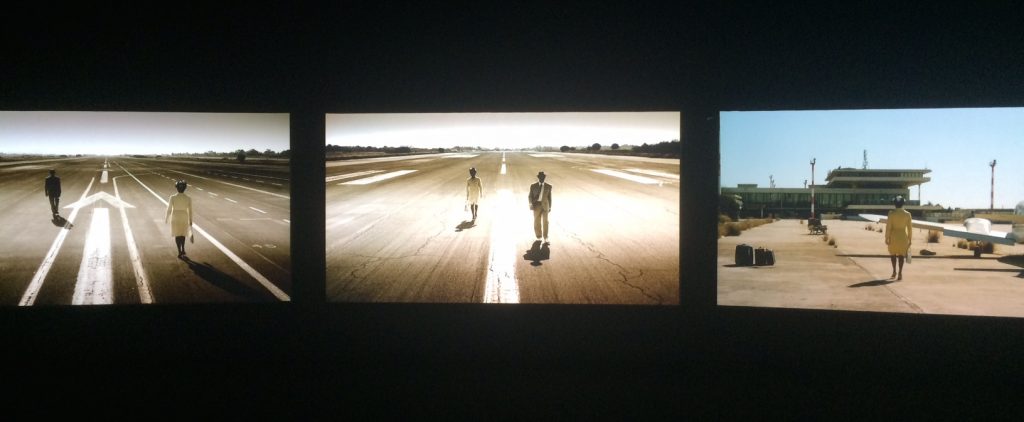

Some of the most striking parallels between ancient and modern artistic concerns were found in works redressing the familiar spectre of globalization, within and without (but here implicitly linked to) the Chinese context. A highlight (shown at the Suzhou Museum of Art) was John Akomfrah’s The Airport (2016). This elegiac and at times surreal three-channel film installation weaves together cinematic, literary and philosophical references in a work meditating upon 20th century Greek history and its recent financial crisis. The potent relevance of such retro-active approaches to addressing concerns of the present in a Suzhouan context is not left to audience speculation. As the exhibition’s introductory text reads: ‘Suzhou Documents will address Suzhou as a centuries-old but also futurist global hub, exploring through artistic and other speculative means a largely unwritten history of trans-cultural encounters between East and West in all their vagaries, conflicting timelines and unforeseeable beauties.’ Other works embraced this dualistic (inwards and outwards) exploratory drive. Of note were works by renowned Chinese artists Liu Ye, Xu Bing, Yang Fudong, and Yue Minjun, which were shown alongside international participants including Thomas Bayrle (Germany), Sheela Gowda (India), Maja Bajević (Bosnia and Herzegovina), Imogen Stidworthy (UK), Willem de Rooij (The Netherlands) and Haegue Yang (South Korea).

The early research phase undertaken by Qing and Buergel in conceptualizing the exhibition is revealing. They began by looking at the historical exhibition ‘1937: Suzhou Exhibition of Documents,’ part of the ‘Cultural Objects from Wuzhong’ exhibition (1937) launched by Keyuan Garden to showcase artworks collected or created by the city’s key artistic protagonists. This landmark exhibition displayed the intellectual and material resources of Suzhou’s artistic luminaries in a conceptual manner, and led to new arteries of thought for participants.

The 2016 instantiation (79 years later) is nonetheless referred to as the ‘first Suzhou Documenta,’ perhaps attesting to an aura of artistic rebirth. The local documents from the ‘Cultural Objects…’ exhibition are offered apparently with this in mind. Buergel’s introduction states that ‘this reactivating Suzhou culture and history is the aim and mission of the exhibition, for this cutting-edge city, with its vision of the contemporary.’

What of the implicit nod to Documenta, Kassel? Buergel states the link is more than in the name, but also in this continual return to the identification of future possibilities in the past. The work, in-fitting with this, is organized under the following key themes: ‘the Time of the Sea and the Empire’; ‘Modernity and Time in the Ming and the Qing Dynasties’; ‘Time and Traditions;’ and ‘Time and the Mind’: The Garden of the Imperial Court’. Despite these expansive themes, Buergel places emphasis on scale and sensitivity. He hopes to have created with Suzhou Documents something ‘small and delicate, echoing the atmosphere of the city itself… not merely a big party for artists and social types, but a place to inspire all visitors.’ Whilst expressing clear reservations about large-scale contemporary exhibitions and their role in society, Qing and Buergel understandably desire a certain international appeal to emerge from the first iteration of this project, amongst those “who have grown understandably weary of biennales and art fairs with all the meretricious charm of a supermarket.”

Attesting to the popularity of the term, and despite the stated (and emphasised) intention of the co-curators to move away from the biennial model, the Chinese mainstream and international art media hailed Suzhou Documents precisely as the creation of a new Biennale, of which there are already several of in China today.

Herein lies a way forward for biennials and the ever growing slew of new cities aspiring to join the over 200 list of mainly small, medium sized cities around the World clamouring to position themselves culturally through the mechanisms of biennale making. The flexibility offered by not calling oneself a biennial at the outset, may offer organisers room to evolve and grow at their own pace, considering changing site specificities and evolving discourses. Qing notes that by bringing together a wide range of new perspectives in history and art, the Suzhou Documenta marks the birth of the new discipline – ‘Suzhou Studies’. However as Buergel notes, “history is not a linear process. It is determined as much by good planning as by luck and chance and therefore tends to defeat the laws of simple chronology.”

Looking forward, Suzhou Documents will have to rely as much on its glorious past as its imagined future, that artists and researchers have been invited to speculate on these outcomes, is a good second coming indeed.

Text by Shwetal A. Patel

Shwetal A. Patel is a founding member of Kochi-Muziris Biennale and PhD scholar at the Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton.

Editing by Henrietta Landells

Henrietta Landells is a London based writer, researcher and curator. Graduate of Oxford University (Anthropology) and the Courtauld Institute of Art (Documentary Media).

Would you like to see your own report from a biennial published on our website? Learn how HERE.