Far from the recognised centres of contemporary art of Mumbai and Delhi, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale has generated a great deal of interest among the art fraternity. Now into its third edition, the Biennale’s ‘creation myth’ still pervades with nostalgia for how – ‘against all odds’ – it came to fruition. Yet, from its first successful edition the Kochi Biennale has been forward-looking and garners strong local and international support. It is widely referred to as a ‘people’s biennale,’ both for its cooperation with the local economy and the very high number of local visitors. Finally, its steadfast, artist-led curatorial approach, with prominent contemporary Indian artists directing each of its editions, is most notable.

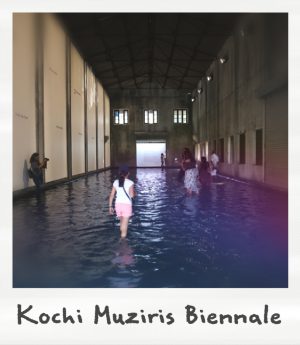

Arriving to Fort Kochi in December 2016, there was a great deal of anticipation as to where this Biennale would attempt to take its audience, as well as the pleasure in returning to the laid-back charms of Kochi’s street life. If the first Kochi-Muziris Biennale, under the curatorship of its founders Bose Krishnamachari and Riyas Komu, was distinctive for its site specificity, and the second for Jitish Kallat’s conceptual ‘journey’ (pulling together different historical and mathematical constellations), the third edition – under the curatorial direction of Sudarshan Shetty – is concerned philosophically, materially and politically with time, it is arguably the most challenging of the three editions.

Moving between the various opening events, you could pick up a mixture of delight and high praise, but also confusion and ambiguity. One frequent response to the latter uncertainties: this was precisely what Shetty wanted – that there was no centrepoint, no required navigation, only multiple possibilities; a biennale that unfolds with time and patience. As Shetty himself puts it: “I see the Biennale as existing in process, something which flows, and I wanted to engage artists whose practices will create works that exist not only for the duration of the Biennale, but into the time beyond.” [1]

Under the curatorial title of ‘Forming in the Pupil of an Eye,’ Shetty’s staging of the Kochi Biennale stretches over 12 official venues. Many of the sites, such as Pepper House, Kashi Art Café and Durbar Hall, have been associated with the Biennale from the start. The iconic Aspinwall House again provides the Biennale with its primary site, presenting key infrastructure as well as the opportunity to make more direct curatorial groupings of related works due to its extensive exhibition spaces. There has been some uncertainty over its continued use, in part because of the resurgence in visitors to Fort Kochi as a by-product and effect of the Biennale, making the building and its grounds primed for commercial development. For this third edition, a number of new venues also appear on the map. A long way down the Kochangadi Road in Mattancherry is TKM Warehouse. Offering large spaces, with ‘white-cube’ rendered walls, this venue has been used with confidence, giving breathing space to just five artists. Out of the 97 artists participating from 35 countries, under half were of Indian origin with a high representation of lesser known Indian artists, mixed with more nationally established artists such as T V Santhosh and Himmat Shah. Notably there are fewer internationally known artists that typically draw large crowds. Perhaps this points to another expression of confidence, with a more determined move to allow the Biennale to be a site of opportunity for emerging artists.

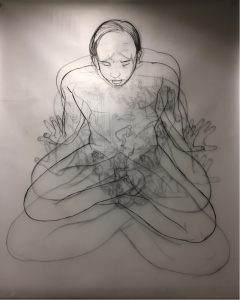

Shetty is much admired for his sensibilities towards art making and materials. The act of making itself is a palpable theme that is picked up in the selection of a number of works. C Bhagyanath’s layered portraits of ‘self’ are created on multiple sheets of semi-transparent paper, with production unfolding in a studio space within Aspinwall House. A short way from this work is Daniele Galliano’s open studio, which similarly he will inhabit for the 108 days of the Biennale. At Pepper House, the sculptor Nicola Durvasula has set herself the task to create 108 objects (one a day), while Erik van Lieshout was assigned a studio space with the supposed idea of working on a film project.

One of the difficulties in producing work over such a long duration and also presenting performative works is that the true process of making and performing can be lost on audiences. Walking into van Lieshout’s space, for example, the artist himself was not present. Taped to the walls in a rather half-hearted manner were various sketches and writings. It was intriguing, yet faintly disappointing. Nonetheless, this edition of the Biennale will be remembered for is its turn to the temporal arts. A particularly powerful and demanding work is Padmini Chettur’s Varnam. A contemporary dance production of three hours, it draws on both the narrative and abstract (or jathi) elements of dance from Bharatanatyam performance, and equally echoes the works of Yvonne Rainer and the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. A melancholic (and at times humorous) spoken narrative ties the performance together with tales from a female perspective, at once romantic and sexualized.

Given the complex history of women’s status in India’s hierarchical social structure, along with a defiant feminist movement since the 1970s, and more recent media attention on continued violence towards women, Chettur’s Varnam provides a radical and multiple re-imagining of the female body. It is certainly ambitious to exhibit such performance work and artworks in the making, not least because biennales tend to attract itinerant, international audiences, who often only attend for a matter of days. But, again, this formatting and curating of works implies confidence, favouring those audiences who might invest more time in Kochi and also those local to the Biennale.

In an interview in The Hindu, Shetty discusses how his curatorial approach has evolved through wide-ranging conversations with practitioners in theatre, poetry, film, music and dance.[2] “I’m not trying to make visual artists out of theatre, music or dance performers,” he explains, but instead, “I’m trying to see how I can keep the integrity of the art form but blur the demarcations.” For the Curator’s Talk, as part of the opening events, Shetty was in conversation with the philosopher Sundar Sarukkai. The notion of ‘multiplicity’ came up repeatedly, and Sarukkai kept referring to various iterations of the curatorial note (as if somehow there was no definitive version, but only a rich palimpsest of views). Shetty’s recursive (and anti-authorial) interest in conversation presents not a dialectical approach, but rather a multiple, layered gathering of meanings.

Interestingly, earlier curatorial statements were much more explicitly conceptual.[3] Shetty spoke of ‘tradition’, for example, as a key and active concept to be integrated within contemporary reality. Yet, in writing the catalogue note, he reverts to a more philosophically enigmatic ‘old story’ of a traveller meeting a Sage who is ‘gathering the world through the pupil of her eye’. This is the Biennale’s underlying motif: “Just as the Sage assimilates image from a plethora of locations,” writes Shetty, “so the Kochi-Muziris Biennale attempts to gather multiple positions.”

During the curator’s talk, in front of a packed audience at the purpose-built auditorium of Cabral Yard, Shetty appeared reluctant to break away from the intimate dialogue with Sarukkai, uncomfortable perhaps to give definitive or unequivocal answers in the ensuing Q&A session. However, if we read this third iteration of the Biennale as bound to temporalities and multiplicities, you come to accept a much slower engagement than any didactic curatorial statement might allow. We might suggest Shetty’s curatorial practice is revealed as being structured precisely as he wishes us to view the work: as layered, cumulative, shifting, multiple, provocative (even at times duplicitous).

Shetty’s focus on the temporality of artworks, art forms and material processes presents a challenge to the biennale format, which typically is anchored by considerations of place and space. Yet, from its inception – and largely due to its artist-led approach – the Kochi Biennale has by no means adopted an‘off-the-shelf’ model. Outside of the metropolitan sphere, Kochi has allowed for a renewed freedom to experience art, with less separation of art and everyday life; and with artists themselves engaged in the making of the event. Unlike some large-scale art events, which we might characterise as ‘legitimating forces’, the Kochi Biennale suggests a humble invitation to ‘build it’ rather than be placed within it. At its best a biennale is greater than a collection of its material objects and sites of display – it bears social connections, it addresses the surrounding local and global politics, it impacts upon educational contexts, and it forges new narratives. All of these things are true of Kochi, and through Shetty’s curatorship we gain further dimensions arising from new provocations of form, content and time.

What remains to be seen, of course, is whether the Kochi Biennale can sustain itself as a progressive force, or whether its own success will place too great a pressure upon it. Kochi – which declares itself the ‘Biennale City’ – has again delivered, with its third and arguably subtlest edition, multiple ways of thinking about this problem, offering as it does a ‘gathering’ of contemporary art that is radically (un)sustainable.

Text by Robert E. D’Souza and Sunil Manghani

Robert E. D’Souza is Head of School and Sunil Manghani is Reader in Critical and Cultural Theory at Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton, UK. They are they co-authors of India’s Biennale Effect: A Politics of Contemporary Art (Routledge, India, 2017).

Would you like to see your own report from a biennial published on our website? Learn how HERE.