Outsiders occupy a unique position to look in, to observe or to critique. Patterns and characteristics that are unrecognisable or even irrelevant to insiders come to the fore; insights gained and buried layers exposed. Such encounters are commonplace in the art world, unremarkable almost. Yet, the depth and complexity brought by these encounters deserves particular attention when they involve artistic transactions, sites of visibility, and history writing – occurring in the context of large exhibitions, such as biennials or triennials.

Can productive tensions be created under such circumstances? How can the ethics of exchange be formulated?

These questions take shape on the grounds of Taragaon Museum in Kathmandu while looking at Colombian-born, London-based Oscar Murillo’s banner announcing in blood red: “the coming of the europeans the coming of the europeans the coming of the europeans.”

Murillo could have put up his banner at any art event. At Taragaon Museum, it was part of the first edition of the Kathmandu Triennale, organised jointly by the city’s Siddhartha Arts Foundation (SAF) and the Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (SMAK), a contemporary art museum located in Ghent, Belgium.

In response to SAF founder Sangeeta Thapa’s invitation to curate the Triennale, SMAK’s artistic director, Philippe Van Cauteren, came up with the theme “My City, My Studio / My City, My Life” for the 17-day event, held from 24 March to 9 April. Van Cauteren assembled over 60 artists, roughly a third from Nepal, and brought in SMAK’s staff to provide technical support for a central exhibition spread across four venues. Murillo’s banner made a pointed reference to this exchange, but also drew attention to the history of restricting foreign influence in the kingdom of Nepal—tourists permitted entry starting only in the 1950s.

During several of the panel discussions, orchestrated by Indian curator Veerangana Kumari Solanki, and in other informal conversations, I heard Nepali artists describe Kathmandu’s rapid urbanisation with a nostalgia, now lost green fields and tight-knit communities. This concern reflected in their work.

For example, Sujan Chitrakar’s (A)Son (2017), cataloguing the artists’s relationship with his father in tandem with his attachment to Ason, their neighbourhood. The pun of the title was layered with a patina of loss and longing in filter-heavy instagram photos on wood blocks, and personal affects placed along side a painted shop sign and drawings of details of temples, all fragments extracted from Ason and imbued with the talismanic capacity to evoke its character.

In Sanjeev Maharjan’s Dialogue Depth (2017), rice and farming tools served as the elements of a family portrait, referring to their now-abandoned hereditary profession. Sheelasha Rajbhandari used photographs, objects and texts about her grandmother to offer an individual and personal narrative of the city. In one interview, the artist’s grandmother said, “I liked Kathmandu better in the past. It was so peaceful.”

But what about the present? Kathmandu is one of the fastest growing cities in South Asia and has seen its population double in the last 15 years. After the massive earthquake of 2015, the urban landscape appears to be caught between the precariousness of collapse and a fever of construction. Dust settles on everything; kicked up by vehicles on bumpy roads, dust is carried by the wind from construction sites, trapped in a valley surrounded by magnificent mountains, and held at bay by masks—a necessity for the city’s inhabitants. Behind the longing for Kathmandu’s past is the acute reality of the arrival of migrants from other parts of the country, displaced during the decade-long civil war that ended in 2006, seeking refuge from environmental changes, or simply in search of a better life. Perhaps we can find these figures in Australian Michael Candy’s allegorical short film Ether Antenna—a collateral project conceived during a residency at the Robotics Association of Nepal last year—which showed robots born by a pristine river travelling to the capital’s choked water bodies and garbage dumps, and traversing construction scaffolds, finally to confront violence and hostility.

As much as Kathmandu’s landscape appears under construction so does the country’s democratic structure: a new constitution was adopted in 2015 and debates about the federal division still continue, often through violent agitation. Through Boston-based Nepali artist Youdhister Maharjan we see a certain fatigue with the ongoing political turmoil, a desire to look away expressed in abstractions made out of cutouts of text and images from copies of the newspaper The Rising Nepal. But, one photo collage among them was telling: there, “…common people waiting for their turn to get their health checked….” are put next to the current prime minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal to mark the 22nd anniversary of the “People’s War,” which Dahal launched as the leader of the communist party.

Depending on who you speak to in Kathmandu, of course, the civil war is described as a “revolution” or a “Maoist insurgency.” What were the gains? What were the losses?

The cast of characters that have exercised an influence during these tumultuous times, and continue to play a vital role today—from international NGOs to the aristocratic class—find their way into Mumbai and Kathmandu-based Karan Shrestha’s narrative painting, whose central protagonist is a young boy letting out a scream of anguish. Shrestha’s Everything at the Centre is a Little Off (2017), also included an arresting four-channel film installation, in which the circular geography of Kathmandu is experienced through dizzying footage shot by a rotating camera, while another screen depicts the violent logic of a city through a film clip featuring a queue of people, each threatening the previous individual with a weapon. Is there any route of escape?

Van Cauteren’s curatorial theme was expansive enough to allow for observations about life in Kathmandu to exist alongside more general commentary on cities. However, this expansiveness lacked focus. The idea of the city seemed so large that even artworks that had tenuous connection with it appeared to have been subsumed within.

It was unclear why there was place for Latvian Diana Tamane’s photograph of a truck called Mom (2016), depicting the artist’s mother in the driver’s seat; or Indian Shilpa Gupta’s Map tracing #3 and #4, wire sculptures of the boundaries of India and Nepal; or Pakistani Waseem Ahmed’s human figure made out of dentures; or German Heide Hinrichs’s The Birds of Nepal [Parting the Animal Kingdom of the East] (2017), an installation that paid tribute to a 19th century ornithological project of the former British resident to Nepal; or even Saurganga Darshandhari’s Mero Aama ko Thaili [My mother’s purse] (2017), paintings of the titular subject.

Van Cauteren asked foreign artists, wherever possible, to create works on site. He painted a vision of having artists to come to Kathmandu with empty pockets. They were given two weeks to execute their projects.

In some cases, this gamble paid off: Bangladeshi Tushikur Rahman was able to capture unexpected encounters with animals and marginal figures in Kathmandu for an iteration of The Sudden Walks (2015-2017), within a week.

An anonymous artist spent time compiling a list of Nepali artists—for all of us to follow up—and covered her entire room at the Taragaon Museum with labels.

Belgian Honoré d’O took the omnipresent wooden beams used to support heritage buildings in Kathmandu as a catalyst for his participatory installation BeTeka (2017), inviting the audience to play the role of this architectural element.

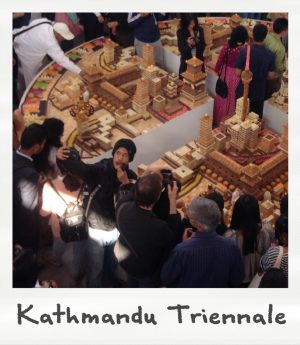

Chinese Song Dong created a city of chocolates and cookies following the plan of a mandala—used in several neighbourhoods in Kathmandu—to create a sugary feast that quickly dissolved into a greedy carnival on opening day.

Romanian Ciprian Muresan built a cardboard city destroyed in a few hours by visitors getting from one floor to the next. Wherever there were interactive artworks, the audience gathered around them.

However, in a number of cases the production constraints provided limited insight into place or concept—Austrian Lois Weinberger made a map with words like ‘migration’ and ‘time’ without articulating why these words mattered here and now; Dutch Henk Visch made drawings depicting copulation as a response to erotic sculptures on temples but without reference to the complex taboos that create the gulf between such art and lived realities; Belgian Gery De Smet collected names of towns ending in ‘ur’ in Nepal, India, Pakistan and Afghanistan on chits and pasted them in a box, highlighting commonalities in the region superficially.

Although Van Cauteren nominated a ‘patron’ artist, the Belgian-born, Mexico City-based Francis Alÿs, as an exemplar of what an artist can do while using the city as a studio, it remained unclear how he served a model for others artists to follow in Kathmandu. The Triennale included Alÿs’s twenty year-old film Paradox of Praxis 1, showing the artist pushing a large block of ice in a street until it melts, turning the labour of mark-making into an exploration of the urban environment; a work of art meant disappear as soon as it was made. However, Alÿs did not contribute a work made in Kathmandu, only leaving the shoes in which he walked in the city as a residue of his time in Nepal. In a public presentation, Alÿs stated that he would need a lot more time to create something in response to the city.

Even if Alÿs was not able to spend the full two weeks of production time in Kathmandu, his anxiety about articulating a response to the city is understandable. It is neither easy nor comfortable to occupy the position of an outsider and offer clear insight or commentary.

The destabilising experience of such encounters was the undercurrent of a collateral exhibition titled Built/Unbuilt: Home/ City curated by Qatar-based Nepali art historian Dina Bangdel. For the project, Nepali artists were taken to Qatar to meet migrant workers from the country, a seemingly explosive choice owing to common knowledge of the many documented cases of the abuse of Nepali workers in the country. Around 400,000 Nepalis are involved in the construction boom related to the 2022 football World Cup. Yet, somehow the focus of the exhibition was far from these problems, highlighting homesickness rather than the struggle for basic rights. Even Hitman Gurung, who used coffins in I have to feed myself, my family and my country (2017), at the Triennale’s main exhibition to address the high toll of worker deaths shied away from criticism showing collaborative family portraits of migrants, and celebrating the co-operation between Nepal and Qatar in the accompanying symposium. Could the involvement—and presence of—the Qatari ambassador at the exhibition have influenced this stance?

Funding is certainly a significant concern for art events of this scale in South Asia, where government support is the exception rather than the norm. To organise the Triennale, SAF founder Sangeeta Thapa had to seek private sponsorship, crowd-source donations, hold auctions and exhibitions, and procure grants from foreign cultural institutes like the Danish CKU and the Dutch Mondriaan Funds. SMAK curator Van Cauteren’s employer even served as a key partner. In addition to the main exhibition, these funds supported performances, activities for children and concerts of traditional music and dance open to the community.

Thapa has been a key figure on the Nepali art scene, having run a gallery since 1987, and organised two editions of the Kathmandu International Art Festival in 2009 and 2012. Some of the donors of the Triennale are members of Thapa’s extended family, influential in the financial and political worlds of Nepal.

Such private initiatives are not unusual in South Asia: in Bangladesh, for example, Nadia and Rajeeb Samdani have begun and funded the Dhaka Art Summit since 2012. Thapa’s work is vital as Kathmandu does not have a robust art infrastructure. There are only a handful commercial galleries, and none with a systematic history of representing artists within or outside the country.

The main venues of the Triennale, spread across Kathmandu are symptomatic of this void: the Taragaon Museum, run by the Saraf Foundation, displays maps and plans and occasionally focuses on contemporary art; the Patan Museum houses antiquities and sustains itself through ticket sales; the Nepal Art Council receives nominal government support and runs on rent from exhibitions.

Among the venues, only Thapa’s Siddhartha Art Gallery is a dedicated space for contemporary art. In such a scenario, the Triennale acquires the function of creating visibility for Nepali artists in the region and abroad. It is difficult to predict what kind of opportunities Nepali artists may find after the first edition of the Triennale as a result of the Belgian collaboration or on account of international attention. Certainly, the benefits can be imagined as mutual—with SMAK having now developed networks in a relatively unexplored art community.

Interestingly, the Triennale did not offer propositions regarding South Asian solidarity. Only Bangladeshi art was represented through a collateral exhibition called Upheavals, curated by Bengal Foundation’s Hadrien Diez and Tanzim Wahab. Dealers and curators from the region were otherwise largely absent.

What role will the Kathmandu Triennale play in the art ecosystem of South Asia? This remains unclear. Or, should Nepal look towards China, South Korea, and other countries in its proximity?

Whether the Triennale chooses to align itself with one regional constellation or another, or facilitates connections elsewhere, the event is an invitation for the artworld to take notice. It can only be hoped that those on the inside—politicians, public and private organisations local to Nepal—also take notice.