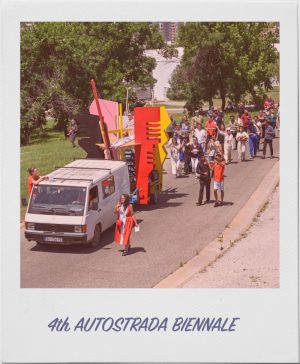

Utopias, what happened to them? The other day I felt like living in one, as I sat and played with a Rubik’s Cube, in a colorful installation constructed by the School of Mutants in dialogue with African artists in Dakar, looking like a ship built by the Memphis Group, ready to sail towards a better world. We rolled through NATO’s old quarters in Kosovo, accompanied by a procession of art workers from all corners of the world, gathered in Prizren for the fourth edition of the Autostrada Biennale, in order to look at some new art works, party, sing, laugh and dance, think again, think better. What else can the art world do in time of war? When dogs are barking, biennale caravans always move on.

The nomadic installation I was sitting in, being too tired after the party the day before, and too keen in resolving the Rubik’s Cube – one of my favorite toys during my childhood in Communist Romania, was in itself functioning like a Rubik’s Cube in constant mutation. This time, it had shifted into a playground for poetry readings by the Roma activist Edis Galushi and a bunch of brilliant musicians who sang Ederlezi, Goran Bregović’s languishing song for Kusturica’s film The Time of the Gypsies. But no, no one seemed to want to be reminded of Kusturica, who according to some, had exoticized the Roma people far too much and paid them far too little. Roma musicians, like all other artists and cultures in constant mutation, (“The Gipsy Group” at the opening appropriated gangsta rap and blues), were playing at every event, inviting the workers of the biennale, the technicians and the guides to dance and sing with the artists, the curators, the critics, and everyone else, from morning to night, amidst long and profound talks and art presentations. This made me think of Marx’s utopian theories on what man has to do in order to avoid the alienation of labor division: “hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, [and] criticize after dinner”.

From a historical point of view, it was wonderful to see so much joy, in a place that has seen so much suffering, still torn by great ethnic conflicts between Albanians and Serbs. The former supported by NATO, the latter by Russia. But is Autostrada Biennale a Marxist Utopia? (I would also say Freudian, you will soon see how) Yes – In the way the division of labor was reorganized and the means of production were “rendered visible”, another Marxist term that the French filmmaker Jean Luc Godard used when he encouraged filmmakers to stop doing films “about politics”, and instead do them “politically”. One of my strongest aesthetic experiences was the construction site in one of the hangars, where one could see some German soldiers’ closets with their playboy girls stickers, in use only some years ago, now waiting to be recycled into artworks. A true utopist is always playful, eclectic, mutant, always on the drift, choosing when and how to settle down. The Autostrada Biennale is also a highly rooted biennale, in its three locales: Prizren, Pristhina and Mitrovica.

The curators of this year’s biennale, who also curated the last edition, are Joanna Warsza and Övül Ö. Durmuşoğlu, two women I’ve long looked up to. Durmuşoğlu for her huge involvement in performative, queer art scenes in Berlin and Istanbul, amongst others. Joanna Warsza, who has recently become a “critical friend”, (that’s the way we call each other in order to keep things transparent), for her curation of Małgorzata Mirga-Tas’s beautiful tapestries at the Polish-Romani Pavilion at the Venice Biennale last year together with Wojciech Szymański and The Berlin Biennale in 2012 entitled Forget Fear that she co-curated together with Artur Żmijewski and the Russian art collective Voina – the first biennale that seriously tried to create a bridge between art and activism. Even Occupy Wallstreet had been invited to the art room. Could art change the world by changing the art world? The biennale became an agora for agonistic conflicts, a luxury that today’s increasingly warlike societies can no longer afford.

Warsza and Durmuşoğlu’s biennale in Kosovo, which is co-curated together with students from the CuratorLab at Konstfack, feels in comparison with the Berlin Biennale intellectual Kriegspiel, both as a soothing, pacifist space for trauma- and memory processing and a joyous call to embrace life here and now, not far from beautiful mixture of euphoric belief in the future and Weltschmerz after the end of the Cold War. The biennale’s title All images will disappear, one day comes from Annie Ernaux’s novel The Years (2008), which evokes the disappearances of both our collective and personal mental images.

The Biennale’s strongest work is done by the Ukrainian artist collective Open Group consists of a pair of colored architectural plan lines in three shades of red, symbolizing the blood spilled by the war in Ukraine, drawn over a yard in the old NATO quarters who might have served for the military helicopter’s or tanks, representing three museums recently bombed by the Russian forces in Ukraine. After listening to Yuriy Biley and Anton Vargas stories about what the museums contained, the third artist Pavlo Kovach, was still in Ukraine, we silently wandered through the maze of the disappeared museums, trying to imagine the images that had disappeared with them.

Another thought provoking work in the biennale is Bella Rune’s phantasmagorical silk thread sculptures hanging from the ceiling in one of NATO’s old hangars, looking like a mix between phalluses, missiles and minarets. Life and death drives, culture and war, beautifully intertwined. In Kostas Bassano’s site-specific installation on Bistrica’s river bank, one can read Walter Benjamin’s famous quote: “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document over barbarism”. During the installation of the piece, the word “barbarism” had fallen into the water and floated along the river currents, which must have surprised the occasional flâneur who could all of a sudden see the word “barbarism” floating down the river. If people will not come to the art, art must come to the people.

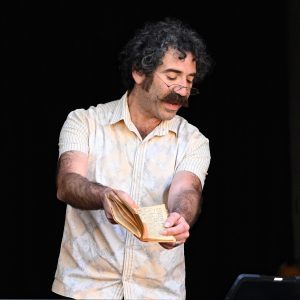

But no, there was no Soviet art totalitarianism here. On a house facade in the city of Prizren, two giant book pages of an Iraqi Jewish prayer book can be seen floating in the wind, made by Michael Rakowitz, who also gave a very touching account of the Jewish exodus from the Arab world of his family members, their lost objects, and their spectral replacements he found on eBay, that he let circulate among the audience. On another building facade, sun-bleached photos from its former activity, the Vatra art gallery, an important resistance meeting place during the Kosovo war, are displayed. In front of a high school, you can take part in the bottle box installation by Ivo Nikic, who built a shelter for play and reflection, based on his childhood memories from Ex-Yugoslavia. Some bottle boxes bear the Coca-Cola logo, which during my communist childhood in Romania represented freedom, now only a symbol of the collectivist era that has passed, because yes, even the so-called war had its advantages in the East – the time we gave each other for the storytelling.

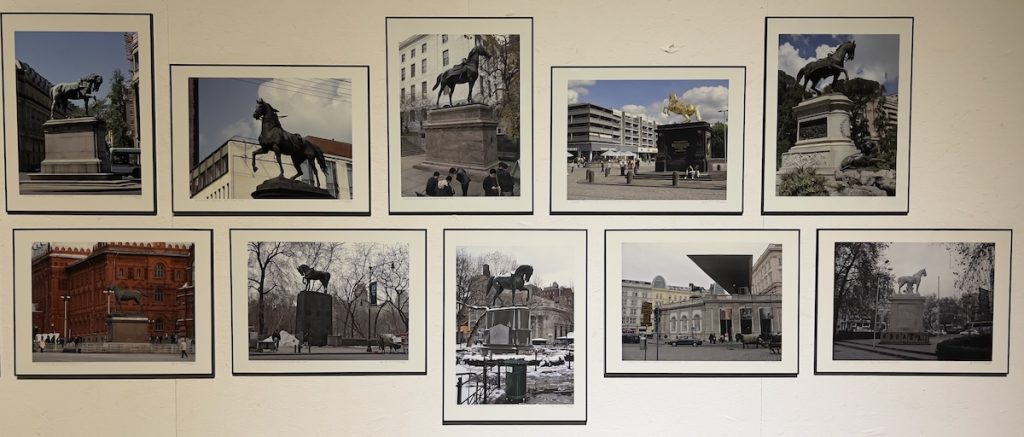

In a photo installation by Luchezar Boyadjiev, one can witness some of the famous equestrian statues, with riders digitally erased by the artist. Only the horses remain. “Your masters have sent you on vacation,” says the artist cheerfully during his presentation, which is an art experience in itself. Each artist is given time and space to talk about their work, which creates a nice de-centering of the otherwise very strong focus on curators and their theoretical frameworks. I am struck by what fantastic storytellers the artists are, their de-colonial way they work with collecting stories, like for example Nathan Gray’s psychonautical memory work with The Juluwarlu Group Aboriginal Corporation, as well as their spot-on humor.

One of the absolute highlights of the biennale is the standup show of the artist Mila Panić, who at a crossroad between Slavoj Žižek and Fran Lebowitz makes fun of everything, including the war in Ukraine, the war in Ex-Yugoslavia, trauma competition, incest, necrophilia, cannibalism, her sex-adventure’s relation to ethnic conflicts, the art world, even her own jealousy towards the sudden interest in Ukrainian artist, especially artists working with photography, who have so great lightening all of a sudden. But what about the artists in Ex-Yugoslavia? According to some, the war in Ukraine is the first war in Europe since The First World War; they must have a non-linear relation to time. I can’t remember, last time I had so much fun at a biennale and realize that this is the first time I’ve seen a stand-up comedian in an art context. How come? Probably because humor, despite our brutal cultural wars, despite all academic efforts, still is seen in the art world who has been for a long time now dominated by curators with broomsticks in their asses, as a lesser art form, even though it is the most effective weapon against both fear, prejudice, racism and above all – stupidity.

In a conversation with architecture and art theorist Yehuda Safran who was visiting the biennale as one of the members of the board, he reminded me of something I had forgotten, namely that Freud claimed that the work of art and the joke have the same structure. Both build up tension first, and then release it. I almost fell off my chair – at this wonderful theory that feels like a joke in itself. I would like to add another dimension – the sexual act, and feel like one day writing about the inherent relationships between art, jokes and sex. All thanks to a biennale where the artists and their tension building and tension releasing art works, made both art feel more important than ever, and life like a big and wonderful tragicomic joke.

Sinziana Ravini is a writer, psychoanalyst and Editor-in-chief of Paletten Art Journal.