Curated by artist’s collective Raqs Media Collective, the 11th Shanghai Biennale takes its starting point as the question “Why Not Ask Again? Arguments, Counter-arguments, and Stories”. A multifarious and speculative question that seeks to utilise the Biennale as a site that can offer the ‘arguments and counter arguments of our time.’ Offering an often pessimistic view of the present spliced with glimmers of hope for the future, especially through technology, the Biennale explores how questions ‘happen’ in our world and posits that art-works carry within them possible futures in as much as they are always drafts for the, as yet, untold future in the present. Perhaps as an inadvertent interpretation of the Biennale’s curatorial conception, Chinese officials at the opening press conference described the success of the Biennale as a shining example of China’s soft power – that is, through its artists and rapidly developing museum infrastructure, China believes it is not only a part of an international dialogue, but shaping and leading that dialogue.

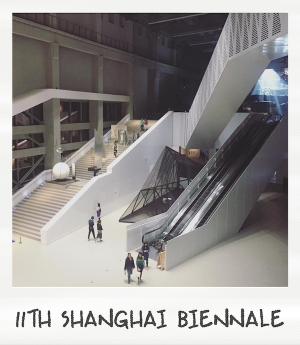

Set in the sprawling and overwhelming Power Station of Art for the second time, the 11th Shanghai Biennale is spread over three floors. The first floor is dominated by the spectacular, large scale and “selfie-friendly” works – none more so than Ivana Franke Disorientation Station (2016) comprised of three rooms installed with distinct lights and shadows, designed to disorientate. Describing itself as being composed of ‘perceptual points’ that “connect the audience to its environment and opens up space for the imagination,” the work symbolised the overwhelming, blinding sensory overload which seems to encourage a self-involved, surface exploration of the works that is hard to shake throughout.

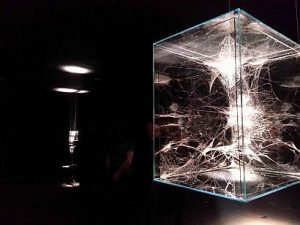

Upstairs over the second and third floors, the curatorial sensitivities of Raqs becomes clearer – a quieter, more poetic reading of the conceit is offered. On the second floor, this extends to an interest in the city, the environment and nature. Tomás Saraceno’s Sonic Cosmic Web (2016) – a clear perspex box within which a spider spins its silk web, illuminated by light and cosmic dust is beautiful, expansive and awe-inspiring; Phuong Linh Nguyen’s Sanctified Clouds (2015) digital prints on porcelain document a series of explosions such that smoke and haze of bombs resemble the natural phenomenon of clouds and mushrooms, and bring to mind the seminal 1976 Bruce Conner film Crossroads, but here imbue the intimacy of lived experience; Liu Yulia’s slow, languid film Black Ocean (2015) is set in an industrial zone in a yardang erosional landforms of the resource rich Gobi desert. Here, machines and animals become mere shadows, while humans are reduced to the functions they enact; there only to operate drills, machines, and vehicles. As the artist writes, “the landscape is vast, the system persistent. This is a hallucinogenic phantom place with one foot rooted in the distant past, and the other marching towards a far future.” Moving up again, the personal and domestic open up further. Exemplary here, Regina José Galindo’s series Estoy Viva (I`m Alive) of performances made from 2001-2016, document the artist occupying a series of configurations – living in full body cast for a week; standing naked in a field while a industrial machine digs a trench around her; in simple gestures, her fragile body speaks of collective violence and humiliation and the potential of resistance.

I visited the main exhibition of the 11th Shanghai Biennale twice – firstly, during the press and professional preview, and secondly, the following day, the first public opening day. Accidentally, I viewed the exhibition first forwards, starting on the ground floor and moving up and then backwards, starting at the top and heading down. This backwards experience of the exhibition made more sense to me: while going forwards I was immediately overwhelmed with visual experiences and encouraged works to be consumed at breakneck speed, going backwards rendered clearer the poetics of the exhibition with explorations of home and human connectivity against the overwhelming collective uncertainty and possibility of beauty and resistance in delicate and fragile ways.

Both days were oversubscribed, I was surprised at the enormous public audiences swirling through the three floors with excitement and wonder. Despite the now all too frequent multilayered curatorial approach, with not only the exhibition’s conceptual conceit to contend with, but “Terminals”, providing ‘points of connection and amplification’ for the exhibition, a seven-layer “Infra-Curatorial Platform”, a “Theory opera”, and “51 Personae” section developed through an open call, much of the work is accessible to non-specialist audiences which felt refreshing. That said, with the ground floor offering so much by way of experiential bombast, the vast exhibition space and the lay of the exhibition privilege the experiential and technological over the analogue and organic. In fact, the Biennale’s curatorial conceit became for me less a political question than one of the Biennale format itself – asking, “Who is the Biennale speaking to, what is it able to say and what do audiences hear?”

Text and images by Rose Lejeune

Rose Lejeune is a curator based in London. Through projects with public museums and private individuals she helps commission and acquire artworks for collections with a focus on context-based, performative and ephemeral practices. Researching immateriality in the art market, Rose is a doctoral candidate in Curating at Goldsmiths College, University of London.

Would you like to see your own report from a biennial published on our website? Learn how HERE.