I offer my words on NIRIN, as an uninvited guest on the lands of the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation; the Boorooberongal people of the Dharug Nation; and the Bidiagal and Gamaygal people, where the 22nd Biennale of Sydney resides. This iteration of the Biennale acknowledges Country by taking a First-Nations, artist-led approach. Brook Andrew, Indigenous Australian artist and Biennale Artistic Director re-thinks typical museum and Biennale tropes through ‘NIRIN’, a term from his Wiradjuri language that translates to ‘edge’. Abiding by its motto “NIRIN is a safe place for people to honor mutual respect and the diversity of expression and thoughts that empower us all,” the exhibition gives voice to under-represented communities, issues and histories, as well as diverse creative spirits, including scientists, chefs, anthropologists and poets. NIRIN is expansive, yet concise, reaffirming interconnections across and between cultures, lands and ideas.

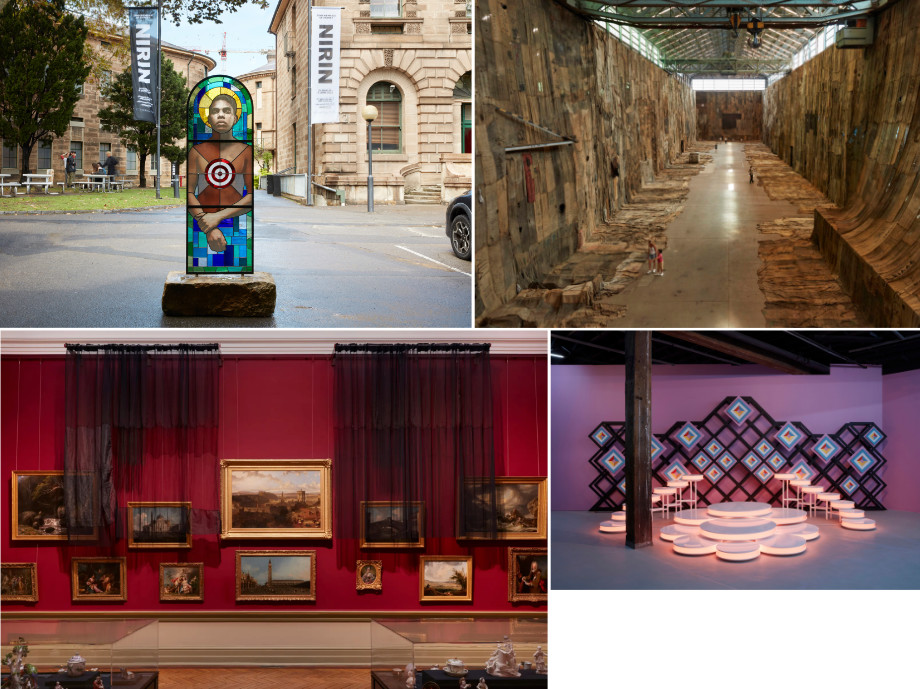

Within this context, it is hard to ignore the loaded histories of each of the six Biennale sites; Art Gallery of New South Wales’ (AGNSW) 1988 extension, built to coincide with the Bicentennial of Captain James Cook’s voyages; Cockatoo Island’s history as a penal colony; the National Art School’s (NAS) former life as the old Darlinghurst Gaol; the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA)’s location at the site of first colonial contact in Australia; Campbelltown Arts Centre’s important surrounding Indigenous lands at the edge of the city; and Artspace’s home within the Gunnery, named after the Royal Australian Navy’s occupation of the building during World War Two. One becomes conscious of how we enter and exit these spaces of living, and often traumatic, memory and how they are navigated by the creative projects inhabiting, acknowledging and reclaiming them. Gateways both reveal and conceal spaces, borders and cultures. These edges of possibility are an important reminder of the awareness and respect we must bring when on the lands of others.

It is often through simple yet potent acts that the 101 exhibiting artists engage with NIRIN. Tania Bruguera and Teresa Margolles remember lives lost in a symbolic yet very palpable way through the performance of skin piercing in Unnamed and falling droplets of water leaving residue on a hot plate in Aproximación al lugar de los hechos. Ibrahim Mahama’s pungent jute sacks and war-ravaged stretchers lining exhibition walls explore the complex histories of trade, displacement and war; while Fátima Rodrigo Gonzales draws attention to overlooked claims of sexual harassment through a colorful, modernism-inspired television set recreated from a popular South American television show.

I first crossed Biennale thresholds at NAS, unknowingly rushing past Tony Albert’s Brothers (The Prodigal Son), 2020. The Indigenous Australian artist’s stained-glass arch features an Aboriginal boy with a red target emblazoned on his chest. Brothers recontextualizes a nearby chapel window, bringing attention to neglected Aboriginal histories. Similar themes are reflected in the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ ornate vestibule, decorated by Wiradjuri woman, Karla Dickens. The installation is largely composed of eccentric caged creatures made from found objects such as feathers and fabric, each featuring a silver caricature head of an Aboriginal Australian woman. Nearby are two large banners of an Aboriginal boxer covered in tattoos and a young Indigenous woman posing in a glittery dress covered in an Australian flag design. A Dickensian Circus, 2020 references dehumanising histories of Indigenous people on display in ‘human zoos’, as part of circus troops and tent-boxing shows in the 1920s-50s. Dickens’ ominous interventions set the tone of the rest of the Biennale works in the nearby Court Galleries. Here artworks are exhibited among AGNSW’s collection displays of European paintings and sculptures, creating room for new interpretation. Ironically titled THERE MIGHT BE NO OTHER PLACE IN THE WORLD AS GOOD AS WHERE I AM GOING TO TAKE YOU, 2020, are Joël Andrianomearisoa’s sheaths of black fabric and lace that obscure several of these paintings. Reminiscent of mourning veils, the Madagascan artist’s haunting, yet delicate junctures question ‘what is really absent and hidden?’

Andrianomearisoa’s shrouds of fabric also infiltrate the MCA, draping down over the words, ‘the mordant wing’ above the main steps. The text commemorates the new MCA wing built in 2012 over the colonial naval docks. Black material continues up the stairwell to a labyrinth of fabric on the third level. Walking between the folds creates a sense of tactile comfort, feeling less ominous than the artist’s AGNSW intervention. Andrianomearisoa subtly reveals and acknowledges conflicted histories through concealing objects and dividing space. Also near the entrance is Erkan Özgen’s video work Wonderland, 2016, featuring Muhammed, a young deaf and mute boy describing his experiences as a refugee from Syria. The child’s visceral gestures and sounds transcend the need for words.

Across waters on Cockatoo Island, Nicholas Galanin’s modest dig site outside the Turbine Hall, Shadow on the Land, an excavation and bush burial, 2020, excavates the shadow cast by a Captain Cook statue in Hyde Park. The Alaskan Tlingit and Unangax̂ artist literally creates a space to bury memorialised colonial histories, while also exposing them – bringing these destructive pasts under archaeological scrutiny.

Among the 36 artists and projects displayed on the industrial Island is a space dedicated to resources on the Plastic-Free Biennale, created by socially-engaged artists Lucas Ihlein and Kim Williams. Striving to holistically embody NIRIN’s focus on environmental care, Biennale staff asked the pair to improve sustainable practices on an organizational level by minimizing use of plastic. The project, composed of implemented strategies and events, highlights the need to shift expectations of what Biennales and museums should look like if they are to be environmentally responsible, including rethinking use of exhibition staples such as vinyl and foam core – NIRIN instead features wall text hung from clipboards and nails. It is more important than ever to look after each other and our planet, especially in light of recent Australian bushfires and today’s heightened global unrest. NIRIN poignantly reminds us of art’s power to challenge the ‘normal’ and make us rethink, acknowledge, take action, and come together.

Once upon a time there were no countries. There was neither centre nor Edge. There was only flow and movement according to nature.

–ArTree Nepal, 22nd Biennale of Sydney Catalogue: NIRIN

Michaela Bear is a curator and writer currently working at RMIT Design Hub Gallery in Melbourne, Australia. She previously worked on the 2017 Honolulu Biennial and has written for a range of publications including Art Asia Pacific, viennacontemporary mag and the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art.